We ask where to find Berlin’s Holocaust Memorial. We thoroughly underestimated what we would actually find.

Our guide said the site was relatively new (2008), and was near the bunker where Hitler directed WWII. But she said we shouldn’t look for the bunker because when she searched, it wasn’t there anymore. She thought the Holocaust Memorial may be near the same spot, close to Brandenburg Gate.

After more than 60 years, a memorial to the six million Jews killed by the German Administration was finally open. Fascist headquarters was razed decades before, but the same site now faces the American Embassy. It presents a powerful exhibit.

After more than 60 years, a memorial to the six million Jews killed by the German Administration was finally open. Fascist headquarters was razed decades before, but the same site now faces the American Embassy. It presents a powerful exhibit.

A field of unmarked stellae, looking like unnamed, up-ended gravestones, covers the block in grey granite. The real power lies just underground.

Attendees enter the underground museum in small numbers. They must pass through a security checkpoint that is like an airport’s. It is sobering to realize that world events leave even this public memorial as a continuing, potential target of world evil.

Attendees enter the underground museum in small numbers. They must pass through a security checkpoint that is like an airport’s. It is sobering to realize that world events leave even this public memorial as a continuing, potential target of world evil.

The crowd is silent as it moves through darkened rooms of evidentiary photographs. Reproduced, damning documentation track the systematic destruction of Jewry throughout Europe and especially in Germany and Europe’s East.

Judi hoped to see someone in the Baltic region or on Russian streets who would look like her. The trail of surviving relatives, however, ended abruptly in the 1940s.

Judi shared the research with us, her fellow travellers. Profound conversations marked our wanderings through what could have been her relatives’ homelands. Her cousin warned, however, and she soon came to her own realization, that there were no survivors in-country for her to recognize. Hitler and his proxies not only murdered them, they destroyed entire settlements along with any record that Jewish inhabitants existed where they did prior to the 1940s.

By the time we arrived in Berlin, Judi was resigned to the finality of her family’s historic, perversely wicked situation.

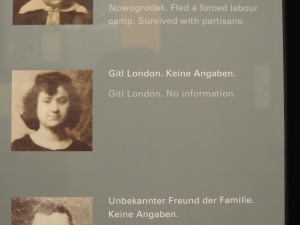

As I turn into another recess of the underground memorial, Annie came running for me. She said that Judi was outside, very undone, and that I must photograph a particular display panel for her. I immediately follow Annie to one of the fifteen family stories selected by the 50-year-old Shoah, an organization which formed to chronicle what could be found of disappeared Jewry.

The displays feature fifteen families from out of two million individuals who died. Researchers isolated a family through oral histories and privately held pictures, who had roots like Judi’s in what now is Belarus. One member of the Kazan family was oddly named London. This mirrored Judi’s cousin’s research which threaded the pre-War past to two sisters. They married two brothers, thereby introducing the surname London to the Kazans, whose own surname later evolved to Coen. The young woman pictured in the museum’s archive undeniably resembles Judi.

The displays feature fifteen families from out of two million individuals who died. Researchers isolated a family through oral histories and privately held pictures, who had roots like Judi’s in what now is Belarus. One member of the Kazan family was oddly named London. This mirrored Judi’s cousin’s research which threaded the pre-War past to two sisters. They married two brothers, thereby introducing the surname London to the Kazans, whose own surname later evolved to Coen. The young woman pictured in the museum’s archive undeniably resembles Judi.

Instead of running into a living relative, here was Judi, face to face with the ghostly possibility of a lost relative. The link is brought to contemporary, public view on the very ground that once sheltered the Exterminator of Judi’s and countless other Jewish families.

It was a possiblity that sent Judi to ground.

Helen sees her exit the underground museum and sees her crumble against the outside granite wall. Annie got word from others and then to me. I take over the task of bringing the discovered evidence back to Judi and ultimately to who her family is today.

Judi regains composure and returns to collect the contact info for the museum curators, themselves a generation later than most of whom they memorialize.

We travellers gather silently around Judi, suddenly a newly formed, extended family of international friends. Some aer young, some old, some religious, some not so much. We regroup in the fading light, above ground, and between the stone columns that wait with their secrets for Judi to find.

We travellers gather silently around Judi, suddenly a newly formed, extended family of international friends. Some aer young, some old, some religious, some not so much. We regroup in the fading light, above ground, and between the stone columns that wait with their secrets for Judi to find.